An old friend of mine is concerned to see Broadway musicals created of Woody Guthrie’s and Bob Dylan’s music. “Is nothing sacred?” he asked.

An old friend of mine is concerned to see Broadway musicals created of Woody Guthrie’s and Bob Dylan’s music. “Is nothing sacred?” he asked.

It is possible we have been having a version of this conversation for more than 25 years.

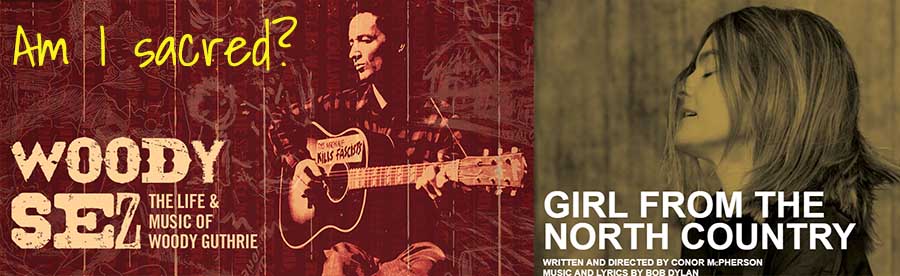

Two musicals sparked this discussion.

Set in Great Depression Duluth, Minnesota, and performed in London, “Girl from the North Country” tells a series of stories through Bob Dylan’s music.

http://variety.com/2017/legit/reviews/bob-dylan-musical-review-girl-from-the-north-country-1202508546/The forty songs in “Woody Sez” tell a story about Woody Guthrie’s own life. This musical has been around for a decade, but it’s currently in New York getting under the skin of Guthrie purists.

https://irishrep.org/show/2016-2017-season/woody-sez/

Jukebox musicals invite (undoubtedly small) audiences to have a great time listening to familiar songs. My friend sees commodification of American folk icons by a mainstream entertainment vehicle.

Yes, and more.

What about Hootenannies and other mainstreaming of folk (vernacular) into Folk (genre)? It’s not like dropping a collection of songs into a new context is a new trend. I could write another dissertation with examples before even reaching back as far as the 19th century.

I could make the argument that Pete Seeger took vernacular music and popularized it, because he did. Why is that acceptable if an off-Broadway jukebox musical isn’t. Purity has some elasticity but not too much. Hootenannies (and the show Hootenanny) were too far for many, but that 50-60-year old argument has cooled. Hootenannies are just part of the folk flow now. Then, they were pure enough for some while not pure enough for others.

Those tears Pete Seeger cried when Dylan plugged in at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival—that is purity losing out to exploring contemporary musical expressions. Oh, no! Re-contextualized vernacular music as a new genre called Folk is too pure to be played through an electric guitar. It wasn’t, of course. Electricity is no a big issue anymore.

Is Woody Guthrie sacred?

Woody Guthrie wanted to find commercial success during his lifetime. He sought it. He certainly found some success on radio. Nothing wrong with that. Woody was no purist. Woody didn’t hold the music that came before him as sacred. He was joyful and angry and passionate. He was completely caught up in his music. He was no saint. He was just a talented guy who told a good story through song. Now, we love him for that.

Obscure and Diminish Political Intent

My friend’s concern is that musicals diminish the “original political intent” of the songwriter.

I wonder how many people sing Woody’s songs or Dylan’s songs without any connection at all to political intent—or how many people create a rich fantasy world of purist political intent when a song is just too slippery to fit in tidy little boxes like that. Songs have a way of becoming new expressions of personal and political consciousness with each new singer or listener.

Some singers add their own political intent to a song and try to hold audiences to their own sacred interpretations of the canon (the religious kind not the musical kind). While refreshingly different from those who take musical performance in the style of the original to be some kind of liturgy, this still takes us too far down the path of the arbitrary sacred.

That’s my song

When Joe Hill wrote to Solidarity (the Wobbly newspaper) in November 1914 to explain why a song reaches people more successfully than a pamphlet, he was helping readers to understand the potential role of song in union organizing. He was explaining the political earworm. He wrote, “a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.” He was writing about how to educate workers through song.

People don’t just carry these songs around like a bag of school books, though.

These songs become pieces of our hearts. The melody starts and stirs up past performances and connections to the politics and the singers that create one long unbroken chain from that first performance to here and now in the center of my universe. “A song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.” Every time we hear or sing a song, we are weaving the context, extending it.

Original Political Intent

What good is original political intent in that context? I see that it gives the grouchy old purist fuel for his fire.

Who is to say what original political intent was anyway? Dylan changed his stories about his songs. Songs slip in and out of contexts. Trying to clean them up and pin them down denies so much rich experience with them.

We could debate songwriters’ intent.

Though, I hope we won’t. I don’t find original intent very interesting.

What I find interesting is the way we make meaning from the songs and the singers, the way we write ourselves into their stories—into our stories.

Bob Dylan wrote himself into Woody Guthrie’s story so convincingly that the story of the Dylan musical is set in the Great Depression before he was born. The era of Guthrie’s struggle becomes the era of Dylan’s music. And, Woody’s songs join the soundtrack of Dylan’s youth, long after Woody’s songwriting was over. The two are woven together. How do you untangle that to prepare any tidy fact patterns for debate about original intent? WHY would you?

The Observer & the Defender

The scholar can go at least two ways with this: the Observer (how do people use this music, this person, this life to make what meaning?) or the Defender (how do people stray from intended meaning, how do later uses fail to be pure). Neither way is completely separate from the other. The defender has to decide what is pure (original intent) in the first place, though, and what is correct use of the original. The defender is one of those making meaning of the original, reframing it for their own purposes. The defender is not disinterested (and I don’t mean to imply that she should be).

Woody and Bob both made use of music and people before them for their own purposes. Each added himself to the story he told, then others came after, claimed the stories, and added themselves. That story chain is the subject of my long-lost thesis.

I look at Dylan and Guthrie in musical theater and want to see who chose to include what details in order to paint what picture of each man. No doubt they will be simpler, flatter. Popular Woody was flatter and easier to embrace than real Woody. Did that diminish him? Would half the people who get a warm, fuzzy feeling singing “This Land” stop singing if the “private property” verse were better known? Is popular Woody less valid because he’s less messy? Questions of validity and purity (questions asked by the defender) seem fraught.

Maybe expecting either of these two people to bear the weight of political intent is expecting too much. As a scholar (and maybe as a therapist, though I am not one), I would say that has more to do with the interpreter than the subject.

Too Sacred for the Masses?

Does mainstreaming through musical theater usurp or diminish? It can only usurp if it’s not valid, right? It can only diminish if the original isn’t strong enough to stand up on its own. Guthrie and Dylan aren’t going to be diminished by musicals. Their music and lives are rich enough to withstand more than that.

Short answer: NO! Nothing is sacred.

I wrote the few paragraphs above to my friend. His response?

“You drew the conclusion I expected.”

Ha! I am happy to be so predictable, I told him.

Schmobjectivity

I know my friend asked about sacred original political intent in a somewhat joking way, but he defended it seriously. I think that is because each of us has written our version of the story, whether that is a published book or the story we tell our friends about why we study what we do. We write ourselves into the songwriters’ stories, into our stories. So, sure, we have ideas about what fits comfortably and what doesn’t, and these are very personal judgments.

No, he tells me, we aim for objectivity.

Sure. We aim for objectivity, and we miss.

We do not have to indulge in the fantasy of disinterested scholarship*. Of course, we as scholars shape the scholarship. Of course, our own positionalities matter.

If a critique shows up in the Guthrie Journal, that is because someone decided to scratch a purist itch. That doesn’t happen unless a personal irritation rises up—just as I wouldn’t have written this post without a purist to reflect against. Dress it up in objectivity, but a critique about the sacred is built on a personal foundation, an assumption of what constitutes the sacred. And, there’s nothing wrong with that.

We are driven by our own personal concerns just as super fans are. We carry these songs as the singers do. Many of us are singers and performers. Our hearts can soar when we hear or sing forty Guthrie songs in a row. We can enjoy the work we do. We matter so much more when we jump into that story and express (rather than suppress) our joy in the music.

You know, I do want to know about the context of the creation of a song. Of course, I do! I don’t want to stop there, though. Songs are alive in every singer and every listener. I want to explore the whole life of a song. That even includes debating original political intent with a purist who claims to know what that is and was.

Loosen up. We study music because we love the music. Let that joy into your scholarship, too.

* At least we don’t have to indulge in the fantasy of disinterested scholarship if we aren’t protecting or aspiring to some sort of position in the academia where that fantasy reigns. #postphd