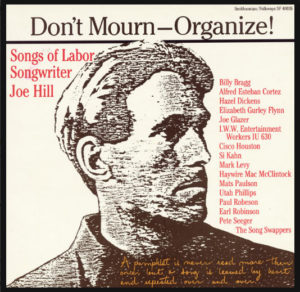

Published 1990 by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Published 1990 by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Smithsonian / Folkways SF 40026

“A pamphlet is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.”

~Joe Hill

I produced this album while working as an archivist at the Smithsonian Office of Folklife Programs (since renamed a couple of times), which included the historical Folkways collection and the contemporary Smithsonian Folkways label. Much of the research was based on my Master’s thesis, The Politicized American Legend of the Singing Hero: Joe Hill, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen (The George Washington University, 1990). Since the album was published in 1990, the references reflect that time period. That was also the year of the 75th anniversary of Joe Hill’s death. I was a member of the Joe Hill Organizing Committee, organizing anniversary events in Utah. I travelled to labor events around the U.S. to promote the album, to talk about Joe Hill, and to sing songs with my Fellow Workers.

The following liner notes are my extended version not published with the recording. I published a few dozen copies of the extended notes—22 pages with a bright red cover—and I hear they are now a collectors’ item. Click on the song names to read extended notes by song. See updates for additions to the original.

Joe Hill (1879 – 1915) was a labor organizer and songwriter for the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.). His songs describe labor struggles with strikebreaking (“Casey Jones—The Union Scab”), the plight of the homeless and unemployed (“The Tramp”), the economic base of prostitution (“The White Slave”). His execution for murder in Utah on 19 November 1915 raise Joe Hill to powerful symbolic status within the labor movement, and many songs and poems were subsequently written about him (“Joe Hill,” “Joe Hill’s Ashes,” “Joe Hill Listens to the Praying”) by other songwriters and authors. Both as a songwriter and as a subject of songs, Joe Hill continues to be an important figure in United States labor history.

The songs, poems, and speeches on this album were written between 1911 and 1989; the performances were recorded between 1941 and 1990. There is a dramatic mix of styles and performance contexts, from an early studio recording of a popular song (“Joe Hill,” Earl Robinson) to an outdoor festival recitation (“Joe Hill’s Last Will,” Utah Phillips) to a college lecture (narrative, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn) to a live concert (“Paper Heart,” Si Kahn) to a contemporary studio recording (“Joe Hill,” Billy Bragg).

When asked “Did you know Joe Hill?” Mac McClintock replied, “Yeah, I knew him well—as well as anybody could be said to know him.” When you have listened to this record, you will know Joe Hill, or at least what he has become. Getting to know Joe Hill is a step in acknowledging our cultural forebears. For many performers—including those appearing on this album—learning and perpetuating stories and songs of Joe Hill is a kind of rite of passage.

Now, 75 years after his death, the name Joe Hill is not known as widely as his influence is felt. Joe Hill is a model and an inspiration for those who still work to organize through music.

“Goodbye, Joe: You will live long in the hearts of the working class. Your songs will be sung wherever the workers toil, urging them to organize.”

~Big Bill Haywood, I.W.W. organizer, 18 November 1915“If there’s one thing that’s characteristic of the labor movement, it is that we never forget our heroes. They continue to teach us through their songs and through their lives and through the things they said.”

~Utah Phillips, 1976 Festival of American Folklife“I do not have much to say about my own person. I shall only say that I have always tried to do the little that I could to advance Freedom’s Banner a little closer to its goal.”

~Joe Hill to Oscar Larson, 30 September 1915, Utah State Prison

Introduction

Notes by Lori Elaine Taylor, Office of Folklife Programs, Smithsonian Institution

When asked, “Did you know Joe Hill?” Mac McClintock replied “Yeah, I knew him well—as well as anybody could be said to know him.” When you have listen to this record, you will know Joe Hill—or at least what he has become. Getting to know him is a step in acknowledging our cultural forebears. For many performers—including some of those appearing on this album—learning and perpetuating stories and songs of Joe Hill is a rite of passage.

Who was Joe Hill? The songs, poetry, and spoken word begins to tell you—describing his life, his death, even the disposition of his ashes. As the first song describes, Joe Hill was a Swedish immigrant (born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund, known later as Joseph Hillstrom) who came to the United States in 1901 at the age of 19, worked at a variety of jobs across North America and in Hawaii, then joined the Industrial Workers of the world. The I.W.W.—whose members were called Wobblies—a radical new movement committed to the formation of a unified worldwide workers’ organization: One Big Union. Joe hill often signed his letters “Yours for the OBU.” He wrote songs reflecting I.W.W. culture and ideology, entertaining his Fellow Workers (as Wobblies addressed one another) while educating them about the evils of strikebreaking (“Casey Jones—the Union Scab”), prostitution (“The White Slave”), and Salvation Army soup kitchens (“The Preacher and the Slave”). He usually wrote songs at the piano, which he called “rattling the music box,” but he also played the violin, accordion, and guitar. In a letter to the editor of Solidarity, from the Salt Lake County Jail, Joe Hill told why he wrote songs as organizing tools:

“A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over; and I maintain that if a person can put a few cold, common sense facts into a song, and dress them up in a cloak of humor to take the dryness off of them, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read a pamphlet or an editorial on economic science.

“There is one thing that is necessary in order to hold the old members and to get the would-be members interested in the class struggle and that is entertainment” (29 November 1914).

Utah authorities arrested Joe Hill in 1914 for the murder of a grocery store owner John Morrison and his son Arling. He was tried and convicted on less than convincing evidence. His supporters considered the charges a class-oriented conspiracy to quiet an instrument of the growing union. The case had already attracted widespread publicity while Joe Hill waiting in jail for the justice he expected, but after he was executed 19 November 1915 it attained a powerful symbolic status within the labor movement. Thirty thousand mourners wearing crimson and singing songs of battle attended his funeral. The day after Joe Hill’s death, one journalist wondered whether his martyrdom might not “make Hillstrom dead much more dangerous to social stability than he was when alive” (New York Times, 20 November 1915). The point was insightful. The I.W.W. certainly used the indignity of Joe Hill’s death to rally members. Now, after 75 years, the name Joe Hill is not known as widely as his influence is felt. Joe Hill is a model and an inspiration for those who still work to organize through music.

The day before his execution, Joe Hill wrote to Wobbly leader Big Bill Haywood, “Don’t waste any time mourning—organize!” Tradition has shortened his request to “Don’t Mourn—Organize!” It is, though, precisely through the rituals of mourning and commemoration that singers, speakers, and artists have organized their audiences. Performers participate in a dynamic musical and political tradition by perpetuating Joe Hill’s ideals and following his example. The songs, the images, the legends and memories of Joe Hill—and other songwriters within this tradition—are used to forge a sense of community.

Singers often repeat stories about Joe Hill to provide a framework for their own performances. These stories are spread through songs and narratives, circulated by means of live performances, or films and recordings, or books and articles. Whatever the medium, those works educate the listener and convey the performers’ respect and affection for their heroes; a spirit of solidarity is engendered among those who participate, sharing knowledge and singing together.

The songwriters who followed Joe Hill are links on a chain of political music, as Pete Seeger wrote in his autobiography (The Incompleat Folksinger. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972): Woody Guthrie wrote “Joe Hillstrom”; Bob Dylan wrote “Song for Woody”; Phil Ochs wrote “Bound for Glory” (about Woody Guthrie) and “Joe Hill” (to the traditional tune Woody Guthrie borrowed for his “Tom Joad”); and Billy Bragg wrote “Phil Ochs” (based on a song about Joe Hill). Songs and stories by performers about their heroes continue to link musical and political traditions among musicians including those above, Pete Seeger, Si Kahn, Hazel Dickens, Utah Phillips, and many others.

Joe Hill alone does not bring together the artists assembled in this collection. Any strong image—an engaging life story such as Joe Hill’s or a moving event like his death by firing squad—can be the occasion for people with similar concerns to shared ideas expressed in song, theater, or works of art. The lives of the songwriters and performers represented here are intertwined not just in musical influences but in social, musical and other activities. These artists travel in and out of common concern for workers’ rights, love of music, and oftentimes stories and songs of Joe Hill.

Further Reading and Listening

Bird, Stewart, Dan Georgakas, and Deborah Shaffer, editors. Solidarity Forever: An Oral History of the I.W.W. Chicago: Lake View Press, 1985.

Foner, Philips S. The Letters of Joe Hill. New York: Oak Publications, 1965.

Glazer, Joe. Songs of Joe Hill. Folkways FA 2039.

Green, Archie. Wobblies and Other Spinners: Laborlore Explorations. Chicago: University of Illinois, in press. [Eventually published as Wobblies, Pile Butts, and Other Heroes: Laborlore Explorations. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993.]

Hampton, Wayne. Guerilla Minstrels: John Lennon, Joe Hill, Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1986.

Kornbluh, Joyce L., editor. Rebel Voices: An I.W.W. Anthology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1964.

Paulson, Mats. Songs and Letters of Joe Hill. Sonet SLP 20.

Smith, Gibbs M. Joe Hill. Layton, Utah: Peregrine Smith Books, 1984. [Originally Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1969.]

Liner Notes by Song

- “Joe Hill,” Billy Bragg 8:26

(Phil Ochs / © 1966 Barricade Music, ASCAP) - “Joe Hill’s Last Will,” Utah Phillips 3:15

(Joe Hill / 1915) - “Joe Hill’s Ashes,” Mark Levy 3:22

(Mark Levy / © 1989 Mark A. Levy, ASCAP) - “The Preacher and the Slave,” Haywire Mac McClintock 3:39

(words: Joe Hill, music: “Sweet Bye and Bye” / 1911) - “Joe Hill,” Paul Robeson 2:57

(words: Alfred Hayes, music: Earl Robinson / © 1938 MCA Music, ASCAP) - “Paper Heart,” Si Kahn 2:21

(Si Kahn and Charlotte Brody / © 1990 Joe Hill Music, ASCAP) - “Casey Jones—The Union Scab,” Pete Seeger and the Songswappers 2:58

(words: Joe Hill, music: Eddie Walter Newton / 1912) - “Mr. Block,” Mats Paulson 3:00

(words: Joe Hill, music: “It Looks to Me Like a Big Time Tonight” / 1913) - “Joe Hill Listens to the Praying,” Joe Glazer 7:20

(Kenneth Patchen / © 1935 International Publishers) - “The Tramp,” Cisco Houston 3:30

(words: Joe Hill, music: George Frederick Root / 1913) - “Joe Hill,” Earl Robinson 2:33

(words: Alfred Hayes, music: Earl Robinson / © 1938 MCA Music, ASCAP) - “The White Slave,” Alfred Esteban Cortez 3:27

(words: Joe Hill, music: “Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland” / 1913) - Narrative, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn 1:06

- “The Rebel Girl,” Hazel Dickens 3:01

(Joe Hill, arranged and adapted with original material by Hazel Dickens / © 1990 Happy Valley Music, BMI) - “There Is Power in a Union,” Entertainment Workers IU 630, I.W.W. 3:16

(words: Joe Hill, music: I. E. Jones / 1913)

Updates